Douglas Turner Ward

A Chronology

The Early Years:

1930 – Born May 5th in Burnside, Louisiana. Father: Roosevelt Ward, a forklift operator.

Mother: Dorothy (Short) Ward, a dressmaker. He was given the name Roosevelt

Ward Jr.

1938 – The family moves to New Orleans, LA, where Ward Jr. attends a two-room

School.

1940 – Attended Xavier University Prep, a black Catholic school.

1946 – Attended Wilberforce University for one year.

1947 – Transfers to University of Michigan. Majors in Journalism. Played football as a

Halfback. After a serious knee injury, he focuses his interests in politics and

Theatre.

1948 – Moves to NYC. Meets Lorraine Hansberry and Lonne Elder III. Joins the

Progressive Party and becomes a Left-Wing political activist.

1949 – Wrote Star of Liberty, a short play about the rebellious slave Nat Turner. The play

is performed before an audience of five thousand people.

Ward is arrested in New York for draft evasion and returned to New Orleans,

LA, where he is imprisoned for three months. His case is appealed.

1951 – Remains in New Orleans for two years while the case is pending. During this

time, writes his first full-length play The Trial of Willie McGee.

1953 – The Supreme Court overturns his draft evasion conviction. Ward moves back to

New York City and attempts to start a literary magazine called Challenge with

Lorraine Hansberry and Lonne Elder III. One issue is published.

Attends Paul Mann’s Acting Workshop and writes for The Daily Worker, a Left-

Wing political journal.

At the Hotel Teresa in Harlem, Ward along with Hansberry and Elder read his

play The Trial of Willie McGee. This reading inspires Elder and Hansberry to try

their hand at writing plays.

Ward joins the Harlem Writers Workshop but leaves after a few weeks because

he felt that their literary outlook was too limiting.

1957 – The Daily Worker closes. Ward’s career in journalism is over. He decides to

pursue a full-time career in theatre.

1958 – Ward gets his first professional acting job at New York’s Circle in the Square

Theatre in Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh.

For acting purposes, Roosevelt Ward Jr. changes his name to Douglas Turner

Ward.

1959 – Performs a small role in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun on Broadway

and understudies Sidney Poitier as a lead character, Walter Lee Younger. Lonne

Elder is also in the show. Robert Hooks joins the cast late in its Broadway run.

1960 – Ward assumes the lead (Walter Lee Younger) in the extended national tour of A

Raisin in the Sun. Hooks and Elder are also in the touring company. The three

become close friends.

1961 – Returns to New York City to play Archibald Wellington in Jean Genet’s The

Blacks at the St. Mark’s Playhouse.

1965 – Robert Hooks produces two short plays at the St. Mark’s Playhouse written by

Ward. The plays were Day of Absence and Happy Ending.

Ward marries Diana Powell.

1966 – Ward wins two Obie (Off-Broadway) Awards. One for writing and one for acting

in Happy Ending and Day of Absence.

Wins Drama Desk Award for Playwriting.

Ward writes an article for The New York Times entitled “American Theatre: For

Whites Only” (8/14). The article stirs discussions about blacks in theatre and

because of this McNeil Lowry of the Ford Foundation invites Ward, Hooks, and

Gerald Krone to submit a proposal for funds to establish a repertory company and

training program for black theatre artists.

The NEC Years:

1967 – The Ford Foundation gives Ward, Hooks, and Krone $434,000 to start the

company. The Negro Ensemble Company (NEC) is incorporated with Robert

Hooks as Executive Director, Gerald Krone as Administrative Director, and Ward

as Artistic Director.

The company opens its first show, Song of the Lusitanian Bogey written by

German author Peter Weiss and adapted by Ward. Controversy and acclaim greets

the opening.

Other plays of that season include Summer of the 17th Doll by Australian author

Ray Lawler, story adapted to the American South by Douglas Turner Ward,

and Daddy Goodness, a French play by Louis Sapan, adapted by the black

novelist Richard Wright.

1968 – Ward directs his first show, which is Daddy Goodness.

Ward and the NEC are publicly attacked in the black press for not producing one

play by a black American playwright in its first season. And also for using the

word ‘Negro’ in its name rather than ‘Black’.

1969 – In their second season, the NEC produces Lonne Elder III’s Ceremonies in Dark

Old Men. Ward plays the leading role and wins a Drama Desk Award for his

performance.

The NEC receives a Tony Award for Special Achievement in the Theatre.

Despite its perceived success, the company is forced to cut down its training

programs due to shortage of grant monies. Later that year, a benefit organized by

Robert Hooks at the Winter Garden Theater on Broadway saves the company from

financial collapse.

Robert Hooks leaves his day-to-day operation at the NEC and moves back to

Washington D.C. to create the D.C. Black Repertory Company.

1970 – Ceremonies in Dark Old Men starring Ward is broadcast in primetime on

ABC TV.

A performance of The Harangues, a short play by Joseph Walker, featuring Ward

in a principal role, is interrupted by a black theatre group protesting its content.

The NEC and Ward come under more fire in black periodicals for being located in

Greenwich Village instead of Harlem and for retaining its white administrator,

Gerald Krone. Ward refuses to respond to these criticisms because he did not

consider them valid.

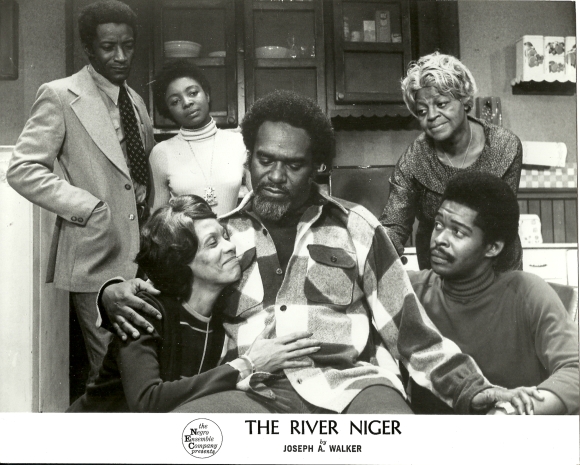

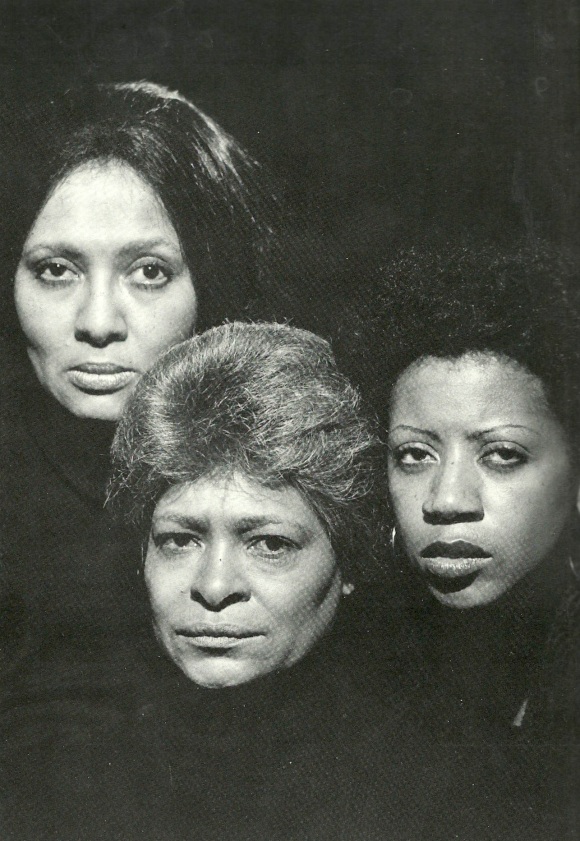

1973 – Ward directs and acts in The River Niger, another play by Joseph Walker. This

becomes the first NEC production to move to Broadway.

The show receives two Tony Award nominations, one for Best Play and one for

Ward for Best Supporting Actor. Ward refuses the nomination because his was

not a supporting part but the lead.

The play receives the Tony Award as Best Play.

1975 – The First Breeze of Summer by Leslie Lee, directed by Ward, becomes the second

NEC play to move to Broadway. It receives a Best Play Tony Award nomination.

Ward receives the National Theatre Conference Person of the Year Award.

1977 – The Louisiana Performing Arts installs Douglas Turner Ward in its Hall of Fame.

1979 – Ward receives an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Fine Arts) from City College of

New York.

Financial constraints force the NEC to drastically cut back on its staff and

production schedule.

1980 – Ward is given the Ebony Magazine Black American Achievement Award for

Accomplishment in Fine Arts.

Home by Samm-Art Williams and directed by Douglas Turner Ward becomes the

NEC’s third play to move to Broadway. It receives two Tony Award nominations.

The NEC moves from the St. Mark’s Theatre in Greenwich Village to Theatre 4

on W. 54th St. in midtown Manhattan.

1981 – Ward receives the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award for

Outstanding Contributions to the Progress of Human Rights.

1982 – A Soldier’s Play, written by Charles Fuller, directed by Douglas Turner Ward,

receives the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Gerald Krone formally resigns his administrative position at the NEC to work in

television news.

1984 – The NEC gets a $100,000 donation from Citibank but is still facing serious

financial troubles.

1987 – The NEC celebrates its 20th anniversary while facing a major financial shortfall.

Ward calls for public support. But some of his announced productions have to be

cancelled.

Ward announces his resignation as Artistic Director and retires the title.

Leon Denmark is named Managing Director of the NEC.

Ward is invited by The New York Times to write a follow-up article to his

“American Theatre: For Whites Only”, assessing the state of African American

Theatre after twenty years. When the article “Counterpoint: A Twenty Year View

of Black Theatre” is submitted, the Times refuses to print it. The article is

ultimately published in Black Masks Magazine.

PBS’s American Masters series broadcasts a documentary, narrated by Ossie

Davis entitled “The NEC: A Company of Excellence”.

1990 – The NEC announces that it will produce Charles Fuller’s ambitious four-play

series about the Civil War and the Reconstruction period collectively known as WE

but financial difficulties make this a difficult task.

1991 – Ward receives an Honorary Doctorate from Columbia College in Chicago.

Ward returns to the NEC as Artistic Director in an attempt to resolve its financial

crisis. He announces in The New York Times that the NEC will have to shut down

if unable to raise $250,000.

1993 – Ward produces and directs Last Night at Ace High, which became the NEC’s last

show under his auspices as Artistic Director.

That same year, the NEC is honored at the National Black Theatre Festival in

Winston-Salem, NC, as an “indispensable cultural and national resource”.

After The NEC:

1996 – Douglas Turner Ward is inducted into the Broadway Theatre Hall of Fame.

(1/22)

1998 – Ward receives Honorary Doctor of Literature from Louisiana State University

2002 – Directs John Scott’s Farma at the Ensemble Theater in Miami, FL.

2003 – Receives Legend Honors Award at the Zora Neal Hurston Festival in Orlando,

FL.

2005 – Ward receives the New Federal Theater’s Award of Excellence at the Town Hall

in NYC.

Ward receives the NAACP Award in Los Angeles, CA.

Note:

This chronology is still evolving because Mr. Ward is still very much alive and active.