The “Bogey” Incident in London

Controversy it seems has constantly been a part of the NEC experience. Right from the beginning when many publicly questioned and challenged its reason for coming into existence, its mission, the choice of plays it produced and of course the use of the word “Negro” in its name. There was controversy about where it was located (in Greenwich Village instead of Harlem) and often about the content of the plays it produced. The Song of the Luistanian Bogey by German playwright Peter Weiss was the first play the new company produced. But it with the author’s permission it had been adapted and completely rewritten by Doug. It opened to tremendous critical acclaim in New York.

In the middle of the second season the Company was invited to participate in the World Theatre Festival in London. The plays chosen for their London debut were The Song of the Lusitanian Bogey and God is a (Guess What?).

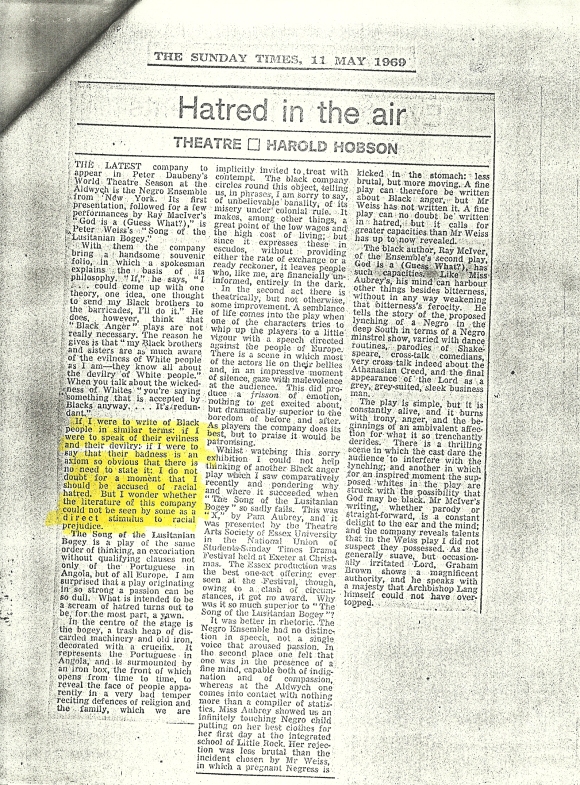

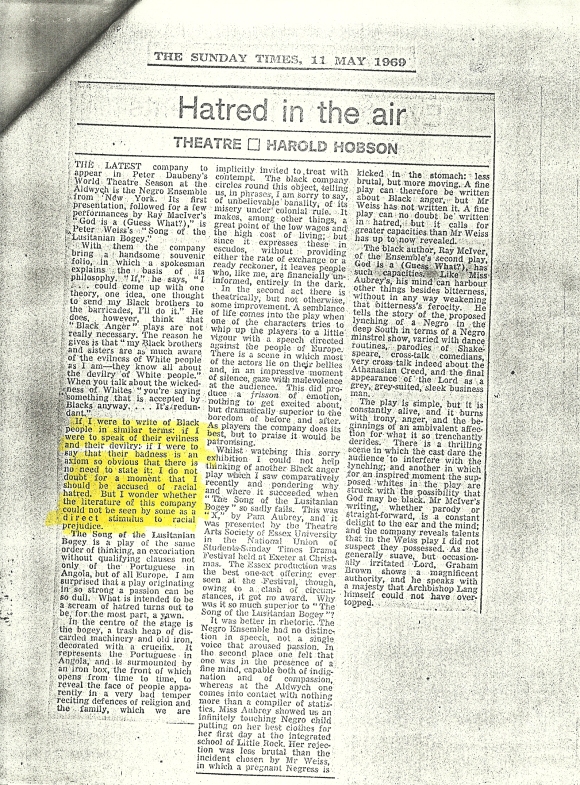

Bogey, the first of the two plays, opened at the Aldwych Theatre on May 5, 1969 and almost instantly, due its political content, there were protests and demonstrations demanding that it should be shut down.In the Sunday edition of The London Times (5/11/69), theatre commentator and critic Harold Hobson wrote, “If I were to write of Black people in similar terms: If I were to speak of their evilness and their devilry: If I were to say that their badness is an axiom so obvious that there is no need to state it: I do not doubt for a moment that I should be accused of racial hatred. But I wonder whether the literature of this Company could not be seen by some as a direct stimulus to racial prejudice.”

Irving Wardle of the Daily London Times (6/6/69) wrote: “It would be hard for me to devise any show more certain of winning white liberal applause than this anti-colonial diatribe performed by a black company: The more so since the target is the Portuguese regime in Angola, and the Company are not Black Arts Revolutionaries, but the more moderate Negro Ensemble Company from New York who are working out their race’s theatrical destiny within the embrace of a Ford Foundation Grant.”

Beyond commentary in the press, there were actual demonstrations in the theatre during performances. There was one particular night that was remembered by its cast members and other personnel many years later.

Ed Burbridge the show’s designer remembered it this way;

“We had a riot in the theatre. Some people who were against what the play was saying attacked the actors from the audience. There was a fight, ushers were throwing people to the floor, actors were crying. After, we went upstairs in the theatre, Douglasgathered us all together and said to us: ‘You’ve done this before in New Yorkand you were very successful with it, but this is probably the most important performance you’ve ever given of this play . . . . It was simply a shock, but it was an awakening, too, for the Company. . . . And after we left the theatre and went back to the hotel . . . someone had scrawled ‘Nigger Go Home’ on the wall. Then it was quite real.”

Several actors in the cast recalled it like this:

Rosalind Cash:

“I don’t know whether it was opening night or during the run of it, there was a riot or something. People were throwing things on the stage, and that had never happened before. I mean, there had been shouts and all that (before). But there were things coming from the area of the balcony, falling on the stage, and I said, ‘Oh, oh I’m going to die with my boots on.’ It felt threatening. And I was in the middle of a protest song and I stopped singing and I heard, I think it was Esther Rolle saying, ‘Sing, damnit! Sing!’ And I stood there defiantly and to where the debris was coming from, and at that moment I really didn’t care. I really didn’t care, cause you see, the subject matter was about the oppression of black people . . . And I was willing to stand there and sing my song . . . . It was a first. It was unique in my career, that things were thrown at us on stage.”

Frances Foster:

“We felt very vulnerable because we had our backs to the audience and we could only hear what was going on. We couldn’t see, and of course we assumed it was the entire audience. But of course, it wasn’t. It was just a small faction that had gotten in to disturb the performance. Deliberately disturb the performance. And (at Intermission) we went backstage. By that time they had called the Bobbies (police), and the Bobbies came backstage and said they would post men in the aisles to keep these people from bothering us. Gerry Krone, Doug and Bobby wanted to know if we wanted to go on with the show. The choice was ours. We said, ‘We’re going to go on.’ And we did . . . So that’s how we dealt with that.”

Esther Rolle:

“The London Bobbies came and threw the whole group out. Well, the adrenaline was so high after that, we continued the show . . . I lost count of the ovations. But that was a performance to remember. . . . It was quite exciting. Very exciting.”

:

Hattie Winston:

“It was the first time I’d ever been out of the country. The first time I’d ever performed out of the country. I experienced joy, I experienced anger. I experienced a sense of solidarity with NEC and with my people. We were picketed. Things were thrown at us. We had a lot of nerve talking about imperialism to the British, inLondon. So they picketed and threw things at us. But a bond was formed. Between the blacks in London and the NEC. People began to take stands. I mean we actually had people who heard about what happened come out and support us. People who normally would not have come to the theatre. They actually came to the theatre to support these nervy black people fromNew York.”

Stage manager Edmund Cambridge:

All of a sudden we heard a kind of rumbling coming from out in the audience and a chanting that kinda grew saying; “Damn lie! Communist!”…The Portuguese contingent that were sitting there began to shout and throw programs and paper and stuff down onto the stage. And Rosalind Cash was standing dead center singing a protest song while this was going on. And you could see a moment of fear in her eyes and she faltered for a moment. And the actors who were in front of her, Norman Bush and the others shouted: “Sing! Sing! Sing!” And I was screaming out: Sing, Roz, Sing!” …And everybody joined together in spirit, I mean you could almost see sparks from the actors out to the audience. And the audience, those that were not protesting, began to feed us with their help in going on with the show. That was a tremendous moment in theatre.”

Michael Schultz was the director and this is what he had to say.

“The actors on stage got totally petrified but they continued to perform because it was the kind of play where you talked back to the audience. There was no fourth wall. So they kept performing until things got out of hand. Everybody was really shaken up because there had never been a violent confrontation in the theatre, in this country. It was quite an experience.”

(All comments were extracted from tape interviews by R. Kilberg.)

God is a (Guess What?), the second play was performed without incident after which the Company took both plays to Rome, Italy, and performed them to lively critical acclaim. But the controversy over Bogey in England continued. On July 2, 1969, the London Times ran a story by a staff reporter that said Sir Elwyn Jones, the Attorney General, asked Sir Norman Skelhorn, Director of Public Productions, to look into the presentation of The Song of the Lusitanian Bogey because Mr. Patrick Wall, Conservative M.P. for Halterprice, asked in the House of Commons whether those responsible for the show would be referred for prosecution for incitement to racial hatred under the Race Relations Act . . . . And a breach of the peace under the Public Order Act.

One official of the Aldwych Theatre said, “In no way could the show be described as racist.” Nevertheless, Sir Elwyn Jones referred the show to the public prosecutor.

On July 5, 1969, it was reported that Sir Elwyn Jones had decided that no useful purpose would be served by taking action against the show. In a public statement, he said that neither he or the Metropolitan Police had received any other complaints about the play which was no longer being performed in the country. And that the Company had returned toAmerica.

-GE.

Note: Some of this material, specifically the quotes, were drawn from interviews conducted by Richard Kilberg.